The Curious Case Of Hiroo Onoda

As 1944 turned to 1945 the Imperial Japanese Army, realizing that the tides of war had turned against them began engaging in new tactics. When their island outposts were close to defeat in conventional warfare, they instructed their soldiers to retreat into the lush jungles that surrounded them and engage in guerilla attacks. The men who were given this assignment were some of the bravest soldiers the world will ever know, as they retreated into the dense forest, knowing full well that they would likely never leave the islands on which they were encamped. The goal of these soldiers was simple; cause as much of a problem for the advancing allies as they could, allowing time for the army to regroup and prepare for the impending invasion of the home islands of Japan.

On February 28th, 1945 after a brief but decisive battle with American force, officer Hiroo Onoda retreated into the jungles on Lubang Island to carry out his orders. For months he carried out attacks on American camps, and local civilians, doing his part to slow down the allied march towards an invasion of Japan.

He and his three fellow soldiers survived on a diet of stolen rice, coconuts, and meat from cattle slaughtered during farm raids carried out when they weren’t attacking nearby Philippine troops. By all accounts, his raids were quite successful. He is known to have engaged in shoot outs with local police, terrorize the nearby farmers, and routinely sabotage military installations on the island.

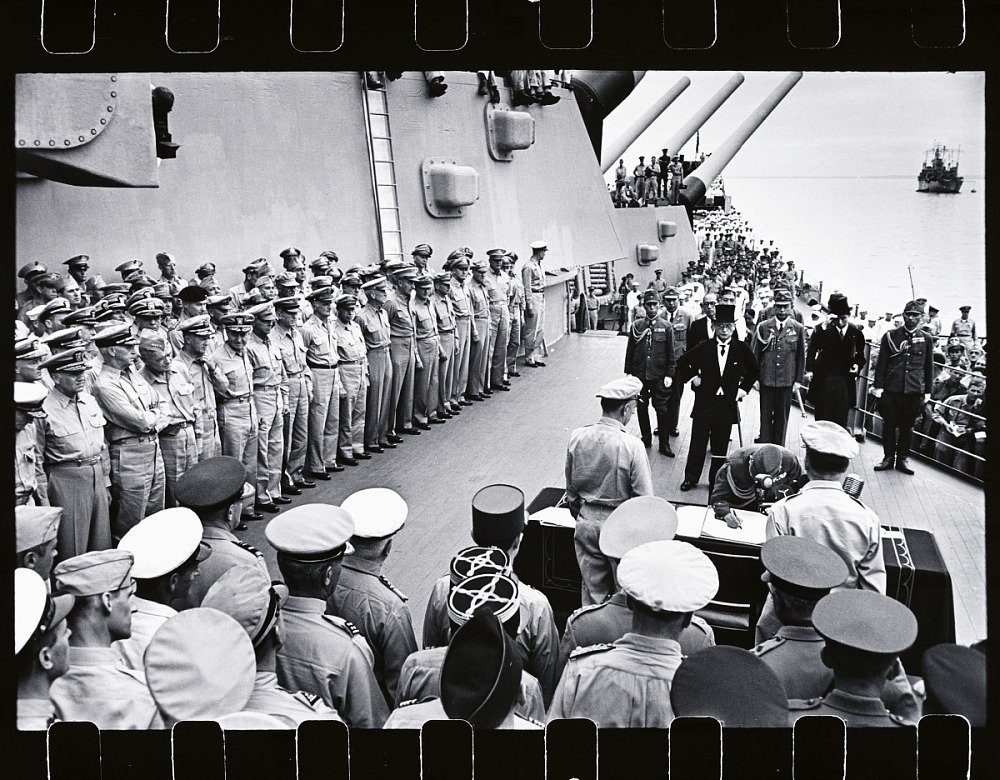

Cut off from any outside communication, Onoda had no way of knowing when the first atomic bomb fell on August 6th. He was also completely unaware of the Japanese surrender a month later on September 2nd. For Onoda, the war was still raging. And for him, it would continue to rage for 29 years.

For 29 years Onoda and his men refuse to believe the leaflets dropped on the island announcing the surrender. To them, the idea of Japan surrendering was unfathomable. They refused to believe it in 1952, when letters from, and pictures of family were dropped on the island. It was not until 1974 that he was found on the island and befriended by a Japanese traveler named Norio Suzuki. Norio returned to Japan with photos of Onoda and was able to convince Major Yoshimi Taniguchi to return with him to the island to fulfill. Promise made to Onoda in 1944: “Whatever happens, we’ll come back for you”. Taniguchi issued Onoda new orders, relieving him of his post, thus ending World War II… 29 years after it ended.

At this point, you are likely asking; “Great story, but what does this have to do with me?” The story of Hiroo Onoda, and his holdout on Lubang Island, is nothing more than an extreme example of the sunk cost fallacy. This fallacy describes our tendency to follow through on endeavor if we have already invested time, effort, or money into it, whether or not the costs outweigh the benefits. For Onoda, he simply could not believe that the empire of Japan would surrender, and he continued to not believe it in the face of many different evidences that the war had indeed ended. For you, it likely will look a little bit different. Today I want to draw your attention to what I think are the three most common instances the sunk cost fallacy I see today.

A Bad Investment

There are not a lot of things more painful than purchasing a stock, only to watch it drop in value. Depending on just how far it drops the pain can be anything from a minor annoyance to an absolute punch in the gut. If you have ever done this, or have watched a friend go through it, you likely thought or heard this phrase “I just have to wait for it to come back up then I can get rid of it”. That is 100% textbook sunk cost fallacy. Logic would dictate that there is no good reason to think that the stock will go back up. The only reason you think that, is because you have a hard time stomaching selling it for less than you paid.

I’ll give you a quick test you can use in these situations to determine if you are falling victim to the sunk cost fallacy. Let’s say your stock drops from $1,000 to $500. The question to ask yourself is this, if someone handed me $500 right now, would I go out use it to buy this stock? If the answer is yes, congrats, you are not falling victim to sunk cost. More often though, asking that question will make you realize that you wouldn’t go buy that particular stock. You may instead think you should buy a different stock with it. Or pay off debt with it. Or go on vacation with it. If the answer is anything but yes, you are coming head-to-head with the sunk cost fallacy, and it is time to cut your losses, and move on.

A Career Change

Imagine for the past ten years you have been teaching math at the local high school slowly climbing the ranks of seniority. You have been working for the past two years to complete a master’s degree which will raise your salary from $50,000 to $70,000 per year. Then out of nowhere a friend reaches out with an offer to come join the company they work for. You wouldn’t be a math teacher anymore, you’d be in software sales, but the job has starting salary would be $120,000 plus bonuses. This one might be a little bit harder to see, but if you look closely, you’ll see the sunk cost.

If you take the new job, you’re essentially throwing away the last ten years spent climbing the ranks, and the last two years you’ve spent going to school at night. Because of all of that time and effort, some people may have a hard time walking away from the teaching job. You’ve simply invested so much time and money into it. Like the first example, ask the question; if you were currently unemployed and looking at two job offers, which would you take. A teaching job that pays $70,000 a year, or the software job that pays $120,000 plus bonuses. Reframing the decision and splitting out the sunk cost can help see the choice in a new way. Some people may still choose to take the teaching job, but most would probably take door number two.

A Broken Down Car

Last week I spent half of a day driving to the middle of nowhere Utah to pick up my sister in law’s car and tow it home. See, I’m the only person in the family that owns a vehicle capable of doing this, so the job fell to me. For those wondering, she had neglected to check her oil levels regularly, the car (it’s an old Honda) had developed an oil leak and had completely run out of oil. When cars run out of oil, bad things happen. Engines get hot, and metal components crack, gaskets blow, and valves fry. Long story short, her car is dead. At least dead, to the point where it would need a new engine to fix it.

Thus, my sister-in-law was left with a decision to be made. Spend $2,500 fixing a car that is worth maybe $3,000, or sell it as is for $1,000 and buy a new car. If you followed those numbers, you likely know exactly what she should do. It’s simple math. If salvage value + repair cost is more that the value of the car in working condition, you don’t fix the car.

It took her over a week to decide that. Why? Sunk cost. See she has owned that car for 5 years. She trusts that car. She has maintained (really it has been me) that car for five years. She is comfortable in that car. In other words she has invested a lot of time and money in that car. The sunk cost in that car is huge. So it took her a while (and some coaching by her dad and I) to separate that sunk cost and make the right choice.

Her story really isn’t unique though. Plenty of people every day face that choice and often make the wrong decision simply because they have a hard time parting with the car, and they have a misguided sense of trust in the car.

Sunk cost is one of the hardest human emotions to fight when it comes to decision making. Our emotions love to blur our vision and lead us into making poor choices that “feel” good. The first step towards learning how to fight these emotions is learning how to recognize them. Hopefully you’re a little better at that now.